Induction Brazing Guide

Metal joining with brazing can produce parts that are stronger than the parent material and also simplifies the manufacturing process.

A number of complex parts can be made easily and repeatedly by combining more simply designed parts. Brazing can be used to join similar metals as well as dissimilar metals. Brazing is used in a plethora of industries including medical, aerospace, automotive and food.

Brazing Topics

Open panels to read more...

-

The Role of Capillary Action

The Role of Capillary Action

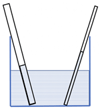

The essential principle of brazing is the flow of the braze alloy due to capillary action. Capillary flow is the ability of a liquid to flow in a narrow gap against traditional forces like gravity.

The essential principle of brazing is the flow of the braze alloy due to capillary action. Capillary flow is the ability of a liquid to flow in a narrow gap against traditional forces like gravity.The force of the capillary action is the same as the wicking of paint in between the bristles of a brush, or in induction brazing the wicking of the braze alloy between the two surfaces of the joint.

-

Essential Braze Alloys

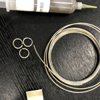

A number of different braze alloys are available depending on the metals to be joined and the temperature required. Lower melting point braze alloys (1100-1400 °F/593-760 °C) are typically silver and copper alloys with the amount of silver varying from 50-20% in the mix.

A number of different braze alloys are available depending on the metals to be joined and the temperature required. Lower melting point braze alloys (1100-1400 °F/593-760 °C) are typically silver and copper alloys with the amount of silver varying from 50-20% in the mix.Higher temperature silver alloys typically have a higher percentage of copper. Even higher melting alloys are made of nickel and other metals and are popular in the aerospace industry.

-

Eutectics of Metal Mixtures

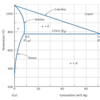

Brazing materials are alloys of two or more metals. The dominant metals in the braze alloys typically determine the melting temperature of the alloy.

Brazing materials are alloys of two or more metals. The dominant metals in the braze alloys typically determine the melting temperature of the alloy.However, when these metals are mixed in particular ratios the combination typically melts at a temperature that is much lower than the alloying metals. The mixture is called a Eutectic.

-

Fixturing Considerations

Holding of the parts during the induction heating process is an art and a science all by itself. It’s important for the holding devices to be capable of withstanding multiple heat cycles without deteriorating.

Holding of the parts during the induction heating process is an art and a science all by itself. It’s important for the holding devices to be capable of withstanding multiple heat cycles without deteriorating.The holding device should also not become a heat sink, robbing the heat from the actual parts being heated. In some applications the fixture is what is heated because the parts are so small that it is impractical to heat them directly.

-

Fluxes Go with the Flow

Flux in a brazing process is an add-on paste or liquid that is applied to the joint area for better flow of the braze alloy. Fluxes are inert salts and do not interfere with the quality of the brazing process.

Flux in a brazing process is an add-on paste or liquid that is applied to the joint area for better flow of the braze alloy. Fluxes are inert salts and do not interfere with the quality of the brazing process.The purpose of the flux is to provide a shield to the joint area so that the metal surfaces being heated do not oxidize.

-

Braze Fillets

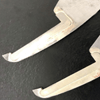

Appearance and the size of the braze fillets has been a topic of considerable debate for some time. While a good visible braze fillet is reassuring that the braze alloy has flowed, the fillet itself does little to improve the strength of the braze joint.

Appearance and the size of the braze fillets has been a topic of considerable debate for some time. While a good visible braze fillet is reassuring that the braze alloy has flowed, the fillet itself does little to improve the strength of the braze joint.The strength of the braze joint is obtained from the lap joint area between the parts being joined, however the appearance of a good braze fillet may act as a simple quality control check for the brazing process.

-

Braze Stop Off

In a number of brazing applications it is difficult to rely just on the capillary action to limit the flow of braze alloy to the joint area. It is often exasperated by the fact that the braze.

In a number of brazing applications it is difficult to rely just on the capillary action to limit the flow of braze alloy to the joint area. It is often exasperated by the fact that the braze.alloy flows towards the heat source, pulling it away from the joint. A few brazing applications can benefit from the use of a braze stop-off compound.

-

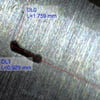

Voids

Voids in braze joints are undesirable. They are also unpredictable and result in quality problems. They reduce the strength of the brazed parts. Often leaks in the braze joints are a result of the voids in the braze joints. The following are common practices for the elimination of voids in braze joints.

Voids in braze joints are undesirable. They are also unpredictable and result in quality problems. They reduce the strength of the brazed parts. Often leaks in the braze joints are a result of the voids in the braze joints. The following are common practices for the elimination of voids in braze joints.- Inadequate time at the brazing temperature for the braze alloy to flow and wick around due to capillary action, some processes require a soak at temperature to allow for the braze to flow.

-

Inert Atmospheres

A number of applications, especially in the aerospace and automotive markets, require temperatures in the vicinity of 2000 °F (1093 °C). Generic fluxes do not work at these elevated temperatures.

A number of applications, especially in the aerospace and automotive markets, require temperatures in the vicinity of 2000 °F (1093 °C). Generic fluxes do not work at these elevated temperatures.In order to protect the oxidation of the metal at these elevated temperatures, vacuum or other inert gas environments are needed. Typical inert gasses include cracked ammonia, nitrogen or argon. Other gasses may also be used for specialized applications.

-

Brazing Application Notes

Over the last 35 years, THE LAB has built a library of over 100 application notes, collecting the challenges our customers have brought to us and the solutions we've provided.

You may find the answers you are looking for!

About Induction Heating

Induction heating is a fast, efficient, precise and repeatable non-contact method for heating metals or other electrically-conductive materials. The material may be a metal such as brass, aluminum, copper or steel or it can be a semiconductor such as silicon carbide, carbon or graphite. To heat non-conductive materials such as plastics or glass, induction is used to heat an electrically-conductive susceptor, typically graphite, which then transfers the heat to the non-conducting material.

Read our 4-page brochure; learn more about how the science of induction technology can solve your precision heating problems.

Precision Induction Brazing

Brazing is a process for joining two metals with a filler material that melts, flows and wets the metals’ surfaces at a temperature that is lower than the melting temperature of the two metals. Protection from oxidation of the metal surface and filler material during the joining process is achieved using a covering gas or a flux material. Brazing and silver soldering are terms that usually refer to the joining process where the filler materials have a melt temperature above 400°C (752°F) to create a stronger joint. Read more in our 12-page brochure.

Induction Heating Work Coils

The work coil is the component in the induction heating system that defines how effective and how efficiently your work piece is heated.

Read our informative brochure explaining the fundamentals of induction coils and their design.

Read: Induction Heating Work Coils

AMBRELL CORPORATION

1655 Lyell Avenue

Rochester, NY 14606

United States

![]() Directions

Directions

T: +1 585 889 9000

F: +1 585 889 4030

Contact Sales

Contact Orders

Contact Service

AMBRELL B.V.

Holtersweg 1

7556 BS Hengelo

The Netherlands

![]() Directions

Directions

T: +31 880 150 100

F: +31 546 788 154

Contact Sales

Contact Orders

Contact Service

AMBRELL Ltd.

Front Suite, 1st Floor, Charles House

148-149 Gt Charles Street

Birmingham, B3 3HT

United Kingdom

T: +44 1242 514042

F: +31 546 788 154

Contact Sales

Contact Orders

Contact Service